Tags

Air Force, Army, father, hero, humor, veterans day, World War II

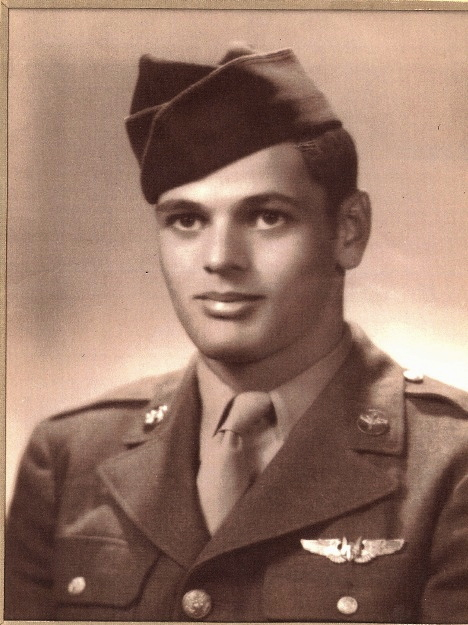

My (sort-of) annual Veterans Day reblog. My father and the rest of his WWII bomber crew are gone, along with most of their amazing generation. But we can still remember their bravery and honor their sacrifice.

At eighteen, you’re immortal.

On the radio last week, I heard a World War II veteran reminiscing about the briefing before D-Day. When they were warned that only one out of three soldiers would make it back, he recalled, every man in the room looked at the men on either side of him and said to himself, “You poor bastards.”

Because sometimes, at eighteen you’re a hero.

Of course, we all know who heroes are. Heroes get up in the morning, buckle on their swash, and go out to save the girl, the regiment, and the free world as we know it. Then heroes take their medals and fade happily-ever-after into the sunset. Don’t they?

Or do heroes go back to school, get up at night with the babies, and worry about the mortgage? Do warriors walk through the house saying, “Who left those lights on?” Do those who once dropped bombs now change diapers with lethal payloads or spend hours keeping that “perfectly good” old clunker running, while their teenagers use the new car? Do the saviors of the free world take out the garbage, mow the lawn, and have trouble getting the microwave to stop flashing 12:00?

Turns out, that’s exactly who heroes are.

I know a hero, but until he turned 70, we never talked about his war five decades earlier. He was an Army Tech Sergeant, a radio-operator on a B-17 bomber back when the Air Force was still part of the Army. His squadron, “Allyn’s Irish Orphans”** flew out of Foggia, Italy, on missions aimed at pinning down the German military machine.

**[“…with usual Army logic, the title was adopted because of the scarcity of Irishmen in the Squadron.”—463rd Bombardment Group History]

When he was drafted, my father was a 17-year-old on Chicago’s South Side, and Franklin D. Roosevelt was president. Holding that draft notice against FDR, he was a Republican evermore. “You can’t draft me, I’m too young,” he told the draft board.

“We’ll bring it up on Friday night,” they replied. His papers came back stamped “Marine.”

“But I don’t like sea travel,” he told them. So he agreed to go if they would let him into the Air Force, which was still part of the US Army. “It was the first and last concession the Army ever made me,” he told me.

He was supposed to get five months of pre-flight training, but they were bumped from their training space after only one month, and he was assigned as a radio-operator on the bomber nicknamed Nobody’s Baby, although not told where they’d be going. “The Army never told us anything. They never bothered,” he told me. “I’ve since read some books to get the feel for what I was doing over there.”

One of the things they were doing was trying to take out German airfield and oil refineries in Romania. They had already made two unsuccessful attempts. But third time’s the charm: Allyn’s Irish Orphans were able to get their bombs on target.

“The Group’s first Unit Citation was awarded after the May 18, 1944 mission to bomb the oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania. Exceedingly bad weather and poor visibility caused the Air Force to send out a recall signal which was received by all bombs groups participating in the raid except the 463rd. As a result, the formation of 35 planes from the 463rd made the run on Ploesti alone. Taking advantage of the situation approximately 150 of Goering’s Yellow Nose fighters attacked. In the ensuing battle, six of the Group’s planes were lost to flak and fighters. The gunners of the 463rd claimed seventeen definites and thirty-two probables. In the nick of time, a large force of P-38s appeared and drove off the Luftwaffe saving the formation from even more losses.”—463rd Bombardment Group History

That day everything went well for my father’s crew and Nobody’s Baby, except for the part where his plane was shot down. “We were the last ones,” he said. “Everyone else had left, but we’d lost an engine and we still had twelve bombs to deliver. We didn’t worry so much about accuracy as about getting rid of those bombs and getting the heck out of there.”

Realizing they’d never make it to Switzerland, they headed for the Russian front lines in Poland. But they were losing air speed. So they threw out “anything droppable” to lighten the plane—the ball-turrets where the gunner had sat under the plane’s belly, their weapons, everything they could pick up, unbolt, or rip out.

They made it to Poland, but the Russians were taking Berlin at the time, and couldn’t organize transport back to Italy. So they were sent to the Ukraine, and had to make their way back through Greece to Cairo and up to Italy.

“Any regrets?” I asked.

“Well, B-17’s had no heated cabins, so we flew with oxygen masks and silk coveralls with electric wires plugged into the plane for warmth, ” he said. “I sure wanted to keep that silk suit, but when we were shot down, they took us for dead and grabbed everything.”

On the way back, they ran into a colonel who was indignant when they didn’t salute fast enough. “You’re out of uniform,” he told them. “Where is your commanding officer?”

By this time, the war in Europe was almost over and Allyn’s Irish Orphans were being moved around, flying transport to ferry homebound troops. “He’s in Foggia, but you better hurry because they’re moving to Naples,” they told the colonel.

“Then I’ll reach him there,” was the reply.

“Well, you better hurry even more, because then they’re moving to Tunis,” they said. They had a few more spots on their itinerary to suggest, but that colonel could tell when the Army had beaten him.

My father kept the clock he managed to get out of Nobody’s Baby, and he had it fixed a few times. It didn’t run by the time we talked about his war, but then, it wasn’t today’s time that it needed to tell.

I’ve always known that anyone who could raise, shoe, and educate ten children was heroic. But I’m proud of this story, and even more proud on Veterans Day to remember a real hero, my father, Bob Figel.

Please join me on this Veteran’s Day in honoring those who offered and those who gave their lives in service to their country.

My father was in Bomber Command in the RAF, just old enough to be there for the last couple of years of the war. I think he volunteered for the RAF so he could have a go at flying and to make sure he didn’t get conscripted into the army! He didn’t talk much about it, but he was a quiet person anyway; he did say he would have been more afraid if he had seen the bigger picture of how many planes were being lost.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That was a lovely tribute. My father was in bomber command, Blue nose squadron, he was a rear gunner on a Lancaster in the RCAF. He was my hero. Still is, even though he’s gone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful Veterans day tribute to your father and those he fought alongside. I knew nothing about my father’s service years. All 20 of them. It makes me a bit sad.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m so sorry that your fathers service took him away from you for so long. It’s a reminder that veterans are not the only ones who sacrifice—their families and friends also give up so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think most people miss that fact, Barb. My mother raised the four of us virtually alone. My son didn’t know his father until he was 18 months old. It’s the way of the world.

LikeLike

Beautiful tribute. My father was in the RAF Bomber Command, also flying B-17s among other kites. I’m ashamed to say I was bored by his repeated telling of his tales – till he finally wrote his memoirs and then I also saw his log book, and realised he, too, was a hero.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your comment made me tear up. You must be so proud of your hero!

LikeLike

Of course! Especially as Bomber Command had to struggle after WWII to be recognised as heroes – they were dissed because of all the civilian casualties. I wrote about him here https://catterel.wordpress.com/2013/03/20/raf-bomber-command-clasp/ and here https://catterel.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/wwii-konigsberg/ Warning: you’ll tear up again!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing these incredibly moving memories. You’re right—I did tear up!

LikeLiked by 1 person